The medieval holy men in England were “riddled with worms,” according to archaeologists. What did they anticipate to discover among a community of individuals who ate their own waste?

Every once in a while, a group of scientists get together and publish a study that reminds us we are merely animals in smart clothes. While one’s hair might be impeccable, nails trimmed, and shoes polished, almost half of humans carry and spread parasitic worms today.

Tapeworms are the big ones, like fire hoses that clamp onto the intestine and mimic it, and they come from drinking water contaminated with animal tapeworm eggs or larvae. But more common are ‘pinworms’ (threadworms), or trichinella. Now, a new study has found medieval monks in England were “riddled with threadworms,” more so than common people.

More than Half of Monks were riddled with Worms

The team of archaeologists from the Cambridge Archaeological Unit recently published their new research in the International Journal of Paleopathology . Piers Mitchell, lead author of the new study, says the research represents the first endeavor to calculate how prevalent parasites were in people with different lifestyles living in medieval Cambridge .

The researchers excavated the remains of 19 friars (medieval monks) at the early 11th century Augustinian friary at Peas Hill in central Cambridge. Soil samples were taken from around the skeletons’ pelvises, which held the remains of worms and larvae. This data was then compared to the results of samples taken from 25 townsfolk from Cambridge.

Excavation of an Augustinian friar with remains of his metal belt buckle in situ (left) and closeup of buckle (right). (Cambridge Archaeological Unit/ Science Direct )

Medieval Monks Getting Down and Dirty in the Garden

Researcher Tianyi Wang performed microscopy to identify the species of the parasite eggs. She said the most common species was “roundworm, followed by whipworm,” both of which are spread among humans by poor sanitary conditions. The study shows that “11 of the friars (58%) were infected with worms, compared with just eight of the locals (32%).” This was an unexpected result because the monks had better washing facilities than common people, who were of lower socioeconomic status.

Furthermore, medieval monks had access to latrines and running water, while common people were leaving their waste in holes in the ground. The team identified the reason for the increased rate of infection among friars as “due to differences in dealing with human waste.” Doctor Mitchell explained that the friars spread their human waste as fertilizer on their vegetables. The larvae are then transferred to the vegetables, leading to repeated parasitical infection.

This Problem Has Gone Nowhere

You are perhaps still struggling to digest what you just read – medieval monks using their own untreated excrement to fertilize their vegetables. Perhaps you are also feeling grateful that you live now and not 900 years ago. But that would all be delusional. Did you know that more than a billion people today still eat food grown in human waste?!

Dr. Elizabeth J. Carlton’s 2015 paper, Associations between Schistosomiasis and the Use of Human Waste as an Agricultural Fertilizer in China said “the eggs of many helminth species (worms) can survive in environmental media.” This research determined the reuse of untreated or partially treated human waste, commonly called “night soil,” promotes the transmission of human helminthiases (parasitic worm infection).

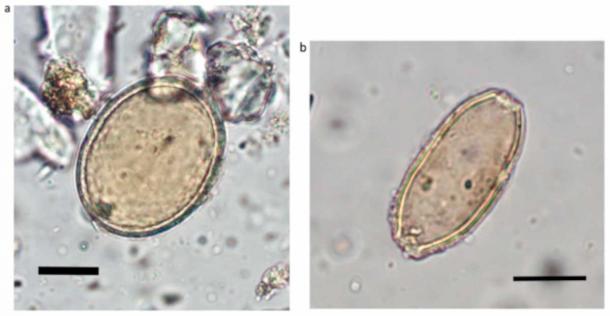

Left: decorticated roundworm egg from burial at All Saints parish cemetery, with dimensions 59 × 45 µm; right: whipworm egg, with dimensions 52 × 24 µm (black bar indicates 20 µm). (Wang, T et al. / Science Direct )

The Battle to Save Chinese Children from Worms

Back in 1998, The Washington Post said the “unholy trinity” of the parasite world is “large roundworm, hookworm and whipworm.” At that time, the number of rural Chinese with hookworm alone was nearly 200 million! The report said the worms were “stunting children’s growth, damaging their mental abilities and making them lethargic and anemic.” It was estimated that stopping the use of night soil would lead to “a 49% reduction in infection prevalence.”

But closer to the present, and to home, according to a 2009 Scientific American article, Columbia University parasitologist Dickson Despommier said “about half the world’s population (over 3 billion people) are infected with at least one of the “unholy trinity”.

Source: ancient-origins.net