When stars die they’re often not alone, and for the first time astronomers have found a companion to a supernova, lingering long after its sibling destroyed itself.

Winds of Change

In the last moments of a massive star’s life, its interior consists of onion-like layers of elements. At the center sits iron and nickel, the last elements a star can fuse before it goes supernova. Its outermost layers are the lightest elements, hydrogen and helium. When the star finally explodes, all those elements get mixed together. Astronomers can study the resulting wreckage to figure out what the star was made of.

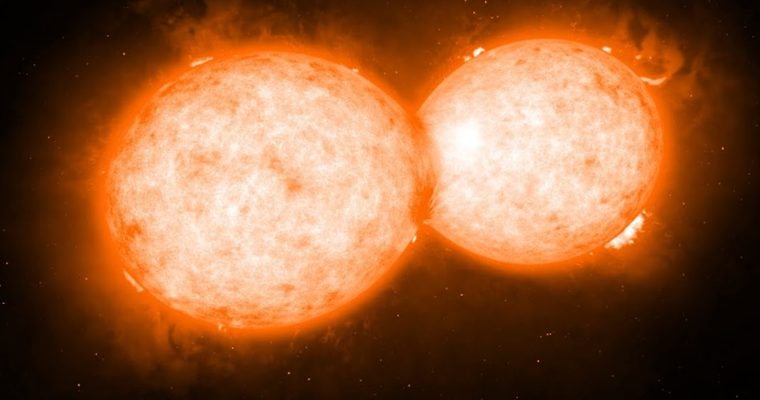

But some supernova remnants lack hydrogen. This suggests that some process removed the outermost layer before the big event. Some older models had predicted that super-hot winds from the star blew away the hydrogen layer, but those models couldn’t explain the observations. Another model proposed that these “stripped” supernovae happen when a star has a companion. That companion has to be big enough and close enough to use its gravity to siphon off the hydrogen before the supernova happens.

While astronomers had long favored this model, until now they had no observations of companions around a supernova event.

“This was the moment we had been waiting for, finally seeing the evidence for a binary system progenitor of a fully stripped supernova,” said astronomer Ori Fox of the Space Telescope Science Institute in Baltimore, Maryland, lead investigator on the Hubble research program that led to the result. “The goal is to move this area of study from theory to working with data and seeing what these systems really look like.”

Diamond in the Supernova

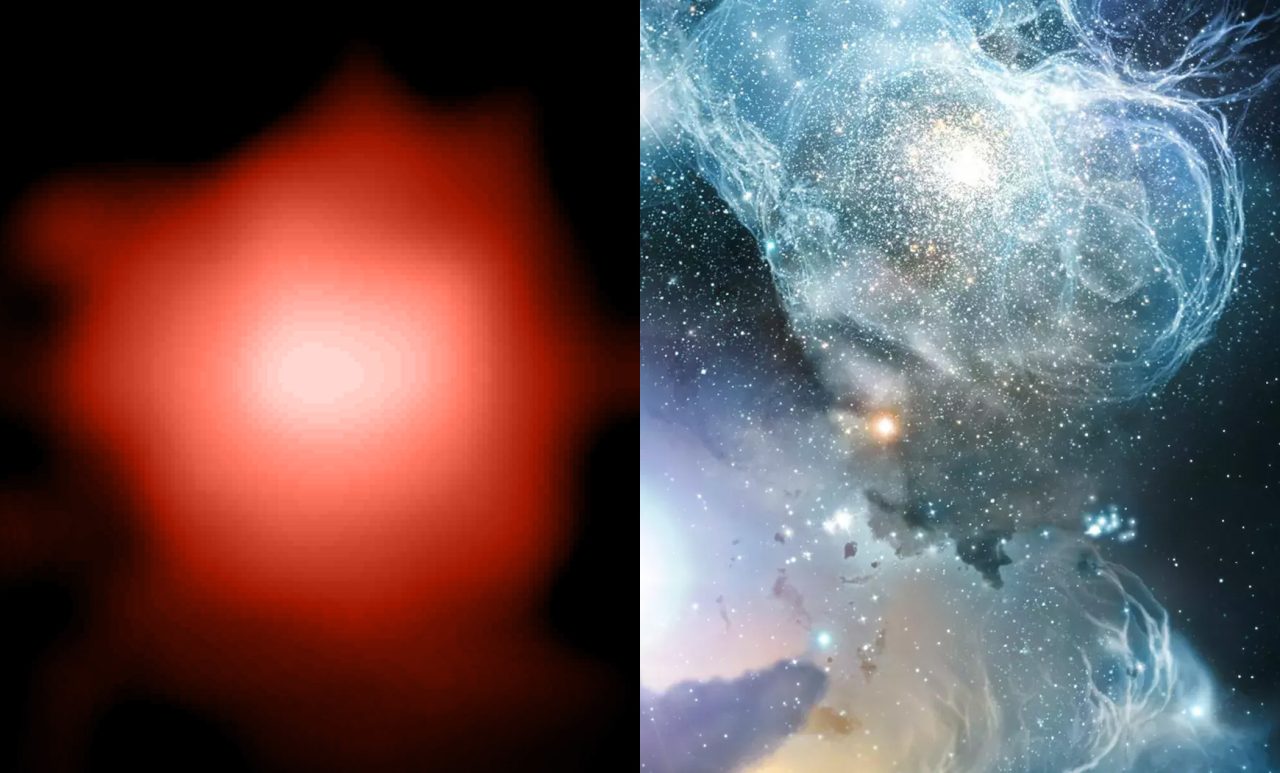

The astronomers found the companion after re-examining supernova (SN) 2013ge. Astronomers had previously studied the fading light of the supernova between 2016 and 2020, but more recently the team re-examined it with the Hubble Space Telescope. They found a bright, constant source of light where the supernova should have dimmed long ago. It was a companion, shining bright long after its sibling star had died.

“In recent years many different lines of evidence have told us that stripped supernovae are likely formed in binaries, but we had yet to actually see the companion. So much of studying cosmic explosions is like forensic science – searching for clues and seeing what theories match. Thanks to Hubble, we are able to see this directly,” said Maria Drout of the University of Toronto, a member of the Hubble research team.

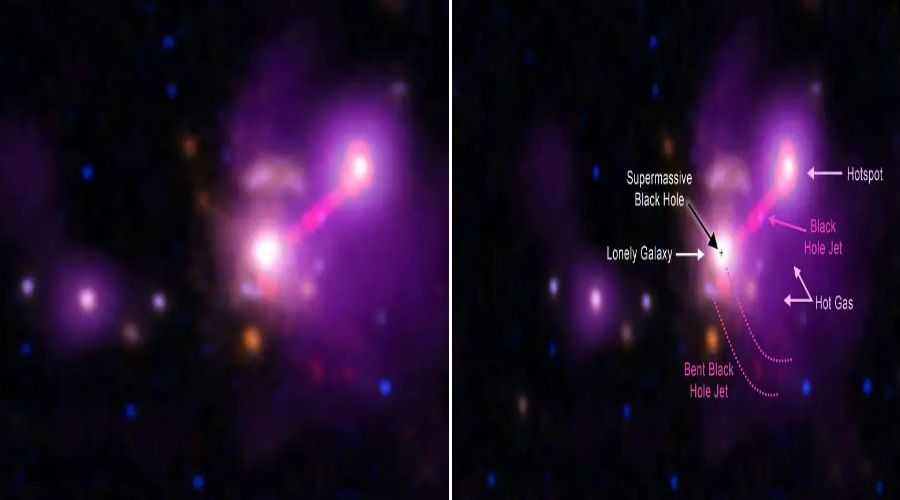

MAXI J1820+070 is a binary pair that has one black hole and one star. The black hole is emitting relativistic jets, and Chandra made a movie of it. Image Credit: Chandra X-Ray Observatory

The observation shows that the scenario of a companion stripping away hydrogen before a supernova is plausible. But beyond that, this observation provides clues to another kind of event: a merger of two exotic objects. The original star left behind either a black hole or a neutron star, and the companion star is also large enough to become a supernova and leave a remnant behind. Someday the two dense objects will collide and merge, releasing a fury of gravitational waves.

“With the surviving companion of SN 2013ge, we could potentially be seeing the prequel to a gravitational wave event, although such an event would still be about a billion years in the future,” Fox said.

Hopefully future observations will reveal more leftover companions, helping astronomers gain a full picture of these processes.

“There is great potential beyond just understanding the supernova itself. Since we now know most massive stars in the universe form in binary pairs, observations of surviving companion stars are necessary to help understand the details behind binary formation, material-swapping, and co-evolutionary development. It’s an exciting time to be studying the stars,” Fox said.