The Book of Revelation is filled with prophetic visions of apocalyptic events. But if the astonishing conclusions of a Biblical researcher from Johannes Gutenberg University Mainz (JGU) are correct, this text may have been doing more than just predicting future disasters. According to Dr. Michael Hölscher, a researcher from the JGU Faculty of Catholic Theology, the Book of Revelation is interspersed with language taken directly from Roman-era curse tablets , written scripts that were meant to bring harm or bad fortune on someone who had somehow cheated, exploited, threatened or wronged someone else.

Rather than just predicting terrifying events, some of the words and phrases included in Revelation may have been meant to bring on those disasters, as a way to seek revenge against Roman authorities persecuting or oppressing Christians in the first century AD, when this final book of the New Testament was composed.

The Book of Revelation’s Surprising Connection to Roman Curse Tablets is Revealed

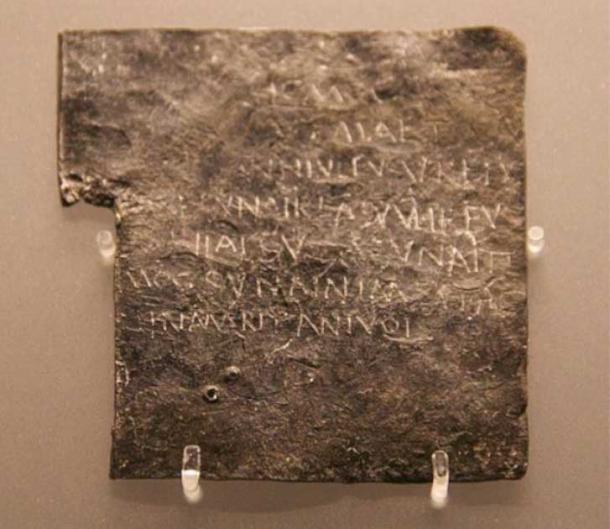

In the Roman world of ancient times, curse tablets were widely used by people from all walks of life. On thin sheets of flattened lead, the vengeful person would inscribe incantations and destructive desires designed to bring calamity and catastrophe into the lives of the targets of the curse. What the former hoped would happen to the latter was often described in vivid detail, and rituals might be performed to make sure the curse tablets would induce the requested effects.

It seems the cursed tablets were meant to gain the favor of various Roman gods and goddesses or spirits of the underworld. The inscribed lead tablets were often placed near graves or in sacred locations believed to be visited by underworld beings or sacred spirits. These mysterious entities had the power to intervene in human affairs, it was believed, and would do so if the right procedures were followed in requesting their assistance.

As for the Book of Revelation, it was composed in the first century AD by an author identified only as John, when Roman authority and influence in the Christian world was pervasive and tinged with authoritarianism. From the perspective of the early Christians, the Roman Empire would have been a worthy target for any curse.

Dr. Hölscher’s study was carried out as part of a JGU-sponsored project entitled “Disenchanted Rituals. Traces of the Curse Tablets and Their Function in the Revelation of John.” As this title reveals, the Dr. Hölscher and his fellow researchers had already considered the possibility that curse language was included in the Bible, and they set out to prove this hypothesis through a more careful and intensive analysis—which they are convinced they’ve done.

Needless to say, the inclusion of curse-related phrases in the Book of Revelation is somewhat surprising, since Christians presumably would have been seeking favors from their own god, the one true god, rather than turning to spirits from other religious traditions for help. But in the first century AD, when Christianity was still young, the old gods and traditions were apparently still respected, even by practitioners of the new religion.

Curse tablet cursing Priscilla from Groß-Gerau: The lead tablet, here the front side, consists of three fragments and is inscribed on both sides with a prayer for revenge in Latin. It probably dates from around 100 AD. (photo/©: René Müller / LEIZA)

In the Days of the Roman Empire, Curse Tablets Were All the Rage

Under Roman law, using curses to exact revenge or gain some type of personal advantage was considered a form of black magic (which is exactly what it was, of course) and was therefore prohibited. But people were convinced that curses worked, and thus they openly flouted the law and produced a cornucopia of curse tablets filled with nasty intentions.

Popular throughout the Roman world, from before the time of the Empire and beyond, curse tablets were created by people from all socioeconomic classes. The casters of the spells and targets of the curses might be sporting opponents, romantic rivals, litigants in court cases, political adversaries, or neighbors upset with each other because one was throwing too many loud parties or allowing their dogs to run loose at all hours. In truth, curses could be issued for just about any reason.

As the Roman Empire grew, the curse tablet culture expanded right along with it. Curse tablets could be found in just about every part of the world the Romans occupied, ranging from Egypt to Britain.

Because they were so common, these inscribed lead sheets have been recovered frequently during archaeological excavations in lands that were once under Roman authority. More than 1,700 of these tablets have so far been discovered at Roman sites, the earliest having been composed in approximately 500 BC and the latest around 500 AD.

To gain a clearer understanding of how the Book of Revelation might have been impacted by the exposure of early Christians to the curse culture, Dr. Holscher and his colleagues performed an extensive analysis of the book’s text. With their advanced knowledge of curse tablet contents, they were searching for precise terminology in the New Testament book that echoed the words of standard curses.

And they found exactly what they were looking for.

“In Revelation, we find wording and phrases that are very similar to those that appeared on curse tablets, although no actual verbatim quotations from the latter appear,” Dr. Hölscher stated.

To illustrate this observation, the German researcher cited a passage where an angel in the Book of Revelation threw a huge stone into the sea, accompanied by a wish for an enemy’s destruction.

“Thus with violence shall that great city Babylon be thrown down, and shall be found no more!” the vengeful angel thundered.

This type of language is often employed in curse tablets, Dr. Hölscher noted. Since the Book of Revelation would have been composed for Christian worshippers living almost 2,000 years ago, those who read such words would have understand their true ritual meaning and significance.

The Roman curse tablets from Bath Britain’s earliest prayers. (Mike Peel ( www.mikepeel.net) / CC by SA 4.0)

The Book of Revelation in History and Curses as a Strategy of Warfare

Christianity in the first century came into conflict with the Roman Empire and its imperial cult, which led to persecution of Christian minorities and a growing mistrust between both sides that would only deepen with the passage of time.

Given this background, it is not surprising that the Romans were the primary target of the invective, bad wishes and forecasts of doom and gloom included in the Book of Revelation . The name ‘Babylon’ was used to represent Rome, and if the wishes for the city of Babylon’s demise expressed by the Revelation angel referenced earlier were in fact a curse, it would have been appropriately directed.

In Revelation, Rome was referred to using this code as the “Whore of Babylon” while its hated emperors (particularly Nero, the chief persecutor of Christians) were identified as “beasts of the sea.” Rome was said to be under the influence of Satanic forces, making it a demonically-inspired threat to the survival of the Christianity community.

“The Book of Revelation contributes to the process of self-discovery, the seeking of a distinctive identity by a Christian minority in a world dominated by a pagan Roman majority that rendered routine homage not only to the emperor but also to the main Roman gods,” Dr. Hölscher explained, placing the book firmly in the context of its time.

In a 2012 interview with NPR , the acclaimed religious historian Elaine Pagels linked the creation of the Book of Revelation with the personal experiences of its author, the man who called himself John. Pagels said that John was likely a refugee who’d been forced to flee Jerusalem after it had been attacked by Roman forces in retaliation for a Jewish rebellion against Roman authority.

“I don’t think we understand this book until we understand that it’s wartime literature,” she declared. “It comes out of that war, and it comes out of people who have been destroyed by war.”

When seen from this perspective, it is easy to see why the Book of Revelation would have included curses lifted from Rome’s own underground religious traditions. This would have been seen as an ironically appropriate way to bring the wrath of the justice down on the heads of the Roman occupiers.

“It is possible that those who read or listened to the words of the Apocalypse of John [Book of Revelation] could readily have seen whole passages, single phrases, or concepts in the light of curse spells,” Dr. Hölscher speculated.

If he is right, the Book of Revelation would have had a special meaning to those who were exposed to its message in the first century AD, a meaning that readers in later eras wouldn’t have been looking for and wouldn’t have been able to decode.