A 1,000-year-old mask discovered on the head of an ancient skeleton was painted using human blood, according to a new study.

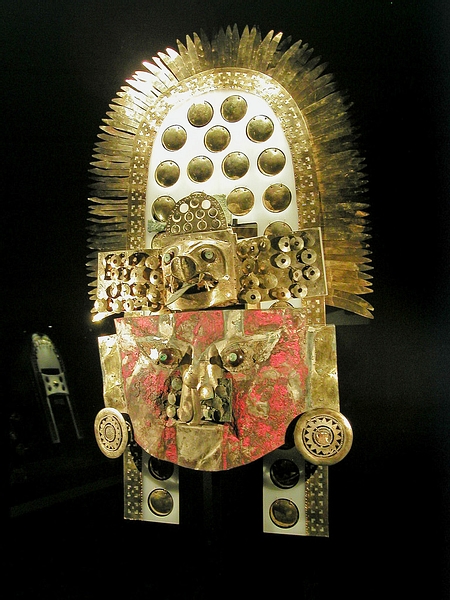

(Image credit: Adapted from Journal of Proteome Research 2021, DOI: 10.1021/acs.jproteome.1c00472)

Archaeologists with the Sicán Archaeological Project unearthed the gold mask in the early 1990s while excavating an ancient tomb in Peru. The tomb, which dates to around A.D. 1000, belonged to a middle-aged elite man from the ancient Sicán culture, which inhabited the northern coast of Peru from the ninth to the 14th centuries.

The skeleton, which was also painted in bright red, was discovered sitting headless and upside down at the centre of a square burial that was 39 feet (12 meters) deep.

The head, which was intentionally detached from the skeleton, was placed right side up and was covered with the red-painted mask. Inside the tomb, archaeologists discovered 1.2 tons (1.1 metric tons) of grave goods and the skeletons of four others: two young women arranged into positions of a midwife and a woman giving birth, and two crouching children arranged at a higher level.

At the time of the excavation, scientists identified the red pigment on the mask as cinnabar, a bright-red mineral made of mercury and sulfur.

A Sicán funerary mask at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York is similar to the one recently analyzed by archaeologists.

But despite being buried deep underground for a thousand years, somehow the red paint — a thick, 0.04- to-0.08-inch (1 to 2 millimetres) layer — had managed to remain attached to the mask. “The identity of the binding material, that had been so effective in the red paint, remained a mystery,” the authors wrote.

In the new study, the researchers analyzed a small sample of red paint to see if they could figure out the secret ingredient responsible for the effective binding.

First, with an infrared spectroscopy technique that uses infrared light to identify components of a material, they figured out that proteins were present in the red paint.

They then used mass spectrometry, a method that can sort different ions in a material based on their charge and mass, to identify the specific proteins.

The red paint contained six proteins found in human blood, the researchers found. The paint also contained proteins originating from egg whites.

The proteins are highly degraded, so it’s unclear what bird species the eggs came from, but the researchers hypothesize that it may have been the Muscovy duck (Cairina moschata), according to a statement.

“Cinnabar-based paints were typically used in the context of social elites and ritually important items,” the authors wrote in the study. While cinnabar was restricted for elite use, non-elites used another type of ochre-based paint for painting objects, the authors wrote.

Archaeologists had previously hypothesized that the skeletons’ arrangement represented a desired “rebirth” of the deceased Sicán leader, according to the statement. For this “desired” rebirth to take place, the ancients may have coated the entire skeleton in this bloody paint, possibly symbolizing red oxygenated blood or a “life force,” the authors wrote.

A recent analysis found that the Sicán sacrificed humans by cutting the neck and upper chest to maximize bleeding, the authors wrote. So “from an archaeological perspective, the use of human blood in the paint would not be surprising.”

The findings were published on Sept. 28 in the American Chemical Society’s Journal of Proteome Research.

Src: archaeology-world.com