Space dust usually makes young stars virtually invisible to our eyes but research undertaken by astronomers used a million images of never before seen objects in an attempt to answer complex questions about the formation of stars.

Astronomers have pieced together more than one million pictures showing never before seen objects in space in an attempt to decipher how stars are born.

A vast “space atlas” of five stellar nurseries – showing young stars in the making, embedded in thick clouds of dust – was captured by the European Southern Observatory (ESO) using a VISTA (Visible and Infrared Survey Telescope for Astronomy).

The research was undertaken to answer complex questions about the formation of stars, which develop when clouds of gas and dust collapse under their own gravity.

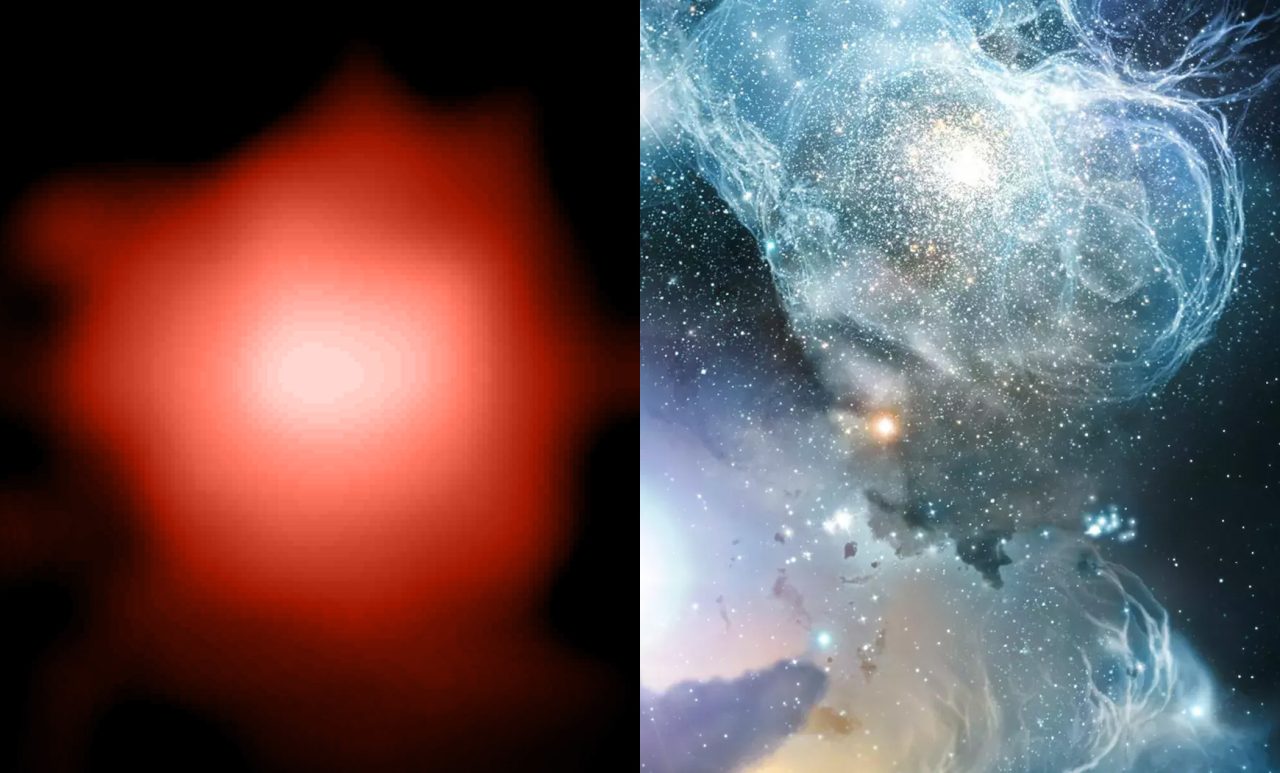

The nearby star-forming region around the Coronet star cluster, in the Corona Australis constellation. Pic: ESO

The exact details of how this happens still remain a mystery – but it is hoped the observations will provide a unique tool to gain a deeper understanding of the process.

Astronomer Stefan Meingast, of the University of Vienna, led the study, named VISIONS, which was published on Thursday in the scientific journal, Astronomy & Astrophysics.

He and colleagues surveyed five star-forming regions – relatively close in space terms to Earth – using the VISTA telescope at the ESO Paranal Observatory in Chile.

More than one million images were obtained over a five-year period from observations of the constellations of Orion, Ophiuchus, Chamaeleon, Corona Australis and Lupus, which are all less than 1,500 light years away.

The images were collated with the use of VISTA’s infrared camera, VIRCAM, to reveal vast, cosmic landscapes including dark patches of dust, glowing clouds, newly-born stars and the distant background stars of the Milky Way.

Dr Meingast said: “In these images we can detect even the faintest sources of light, like stars far less massive than the Sun, revealing objects no one has ever seen before.

“This will allow us to understand the processes that transform gas and dust into stars.”

Image:The Lupus 3 region in visible light Pic: ESO

Image:The Lupus 3 region in visible light Pic: ESO

Image:An infrared view of the the Chamaeleon constellation Pic: ESO

The study will see baby stars monitored over several years to measure their motion and discover how they leave their parent clouds, said fellow University of Vienna astronomer, João Alves.

But this is not an easy task – with the view of shifting stars from Earth likened to the width of a human hair seen from 10 kilometres away.

Study co-author Alena Rottensteiner, a PhD student at the University of Vienna, said: “The dust obscures these young stars from our view, making them virtually invisible to our eyes.

“Only at infrared wavelengths can we look deep into these clouds, studying the stars in the making.”

Image:The Chamaeleon constellation Pic: ESO

The VISIONS project is set to keep astronomers busy for many years to come.

“There is tremendous long-lasting value for the astronomical community here,” said study co-author, Monika Petr-Gotzens, an astronomer at the ESO in Garching, Germany.

VISIONS will also lay the foundations for future observations with other telescopes, such as the ESO’s Extremely Large Telescope (ELT) which is currently under construction in Chile.

Dr Meingast concluded: “The ELT will allow us to zoom into specific regions with unprecedented detail, giving us a never-seen-before close-up view of individual stars that are currently forming there.”