Satellite trackers show two of the animals are now ‘well south’ of Tasmania

Satellite trackers show two of the animals are now ‘well south’ of Tasmania

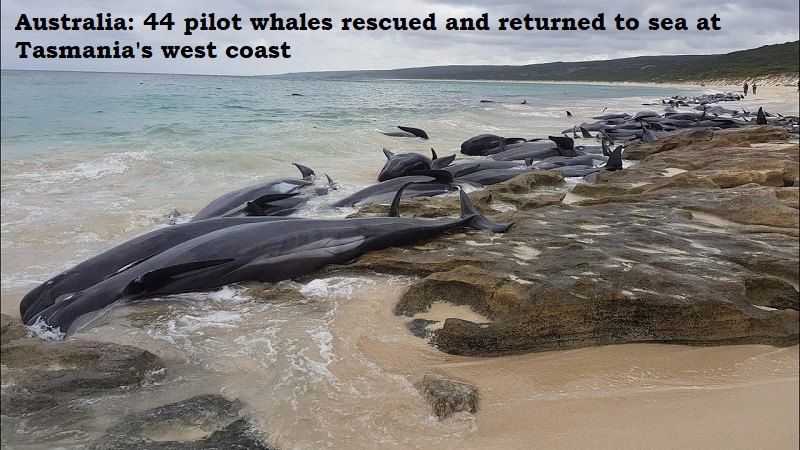

A mission to rescue scores of pilot whales found still alive on a beach after a mass stranding on Tasmania’s west coast has ended with 44 of the animals towed back into the ocean.

Preliminary data from satellite trackers on two of the rescued pilot whales – which are actually large oceanic dolphins – show they are now “well south” of Tasmania.

More than 230 pilot whales were reported stranded at Ocean Beach, west of Strahan, last Wednesday but more than 170 were already dead when rescuers arrived.

State government personnel and volunteers from the community and the local salmon farming industry worked alongside vets to rescue the animals, towing them one-by-one into waters off the coast.

Almost 200 dead whales were tied together and on Sunday pulled out into the ocean, where authorities said they were expected to drift south, though some could float ashore. Two carcasses remain on the beach.

Preliminary data from satellite tackers on two of the rescued whales showed they were now swimming well south of Tasmania.

Nic Deka, the incident controller for the rescue, said: “This is positive news as this indicates that many of the rescued whales have been successfully released back into the Southern Ocean.”

Deka thanked colleagues from the Department of Natural Resources and Environment Tasmania, as well as salmon industry staff, volunteers and the Strahan community and local council for their help. Access roads have re-opened.

Authorities warned carcasses could wash up in the coming weeks and surveillance flights would be monitoring nearby beaches.

The stranding came two years to the day after the biggest recorded mass whale or dolphin stranding in Australia at the same location. 470 pilot whales were found in Macquarie Harbour and on Ocean Beach.

Experts say the cause of the stranding may never be known. But the coastline near Strahan is known as a “whale trap” because of the frequency of strandings there.

Tissue samples were taken and necropsies carried out on the dead whales to rule out any unnatural causes for the deaths.

But it was thought that some of the whales in the pod may have been drawn in, away from the deeper waters where they live, either because of sickness or to chase squid.

Once close to the shore, the sloping beach can confuse the whales’ echolocation. Because the whales can communicate with each other, and form strong social bonds, experts said this could have seen hundreds follow the disoriented or sick whales.

Authorities asked for any sightings of stranded whales or carcasses in the region to be reported to a whale hotline at 0427 WHALES.

… as 2023 gathers pace, and you’re joining us from Vietnam, we have a small favour to ask. A new year means new opportunities, and we’re hoping this year gives rise to some much-needed stability and progress. Whatever happens, the Guardian will be there, providing clarity and fearless, independent reporting from around the world, 24/7.

Times are tough, and we know not everyone is in a position to pay for news. But as we’re reader-funded, we rely on the ongoing generosity of those who can afford it. This vital support means millions can continue to read reliable reporting on the events shaping our world. Will you invest in the Guardian this year?

Unlike many others, we have no billionaire owner, meaning we can fearlessly chase the truth and report it with integrity. 2023 will be no different; we will work with trademark determination and passion to bring you journalism that’s always free from commercial or political interference. No one edits our editor or diverts our attention from what’s most important.

With your support, we’ll continue to keep Guardian journalism open and free for everyone to read. When access to information is made equal, greater numbers of people can understand global events and their impact on people and communities. Together, we can demand better from the powerful and fight for democracy.