Aster tataricus

The Tatarian aster, Aster tataricus, is a non-native perennial in the large Asteraceae family that includes chrysanthemums, daisies, and sunflowers.

It is an aggressive grower prized for its late season lavender-blue, yellow-centered blossoms. In this article, you will learn all you need to know to cultivate Tatarian aster in your outdoor landscape.

Cultivation and History

A. tataricus has an upright profile of sturdy stems that are usually self-supporting. The foliage is dense at the bottom, with paddle-shaped leaves up to 2 feet long that get smaller as they grow up the stem. At first, it looks like you have a fine crop of leafy green vegetables, but then the stems begin to lengthen.

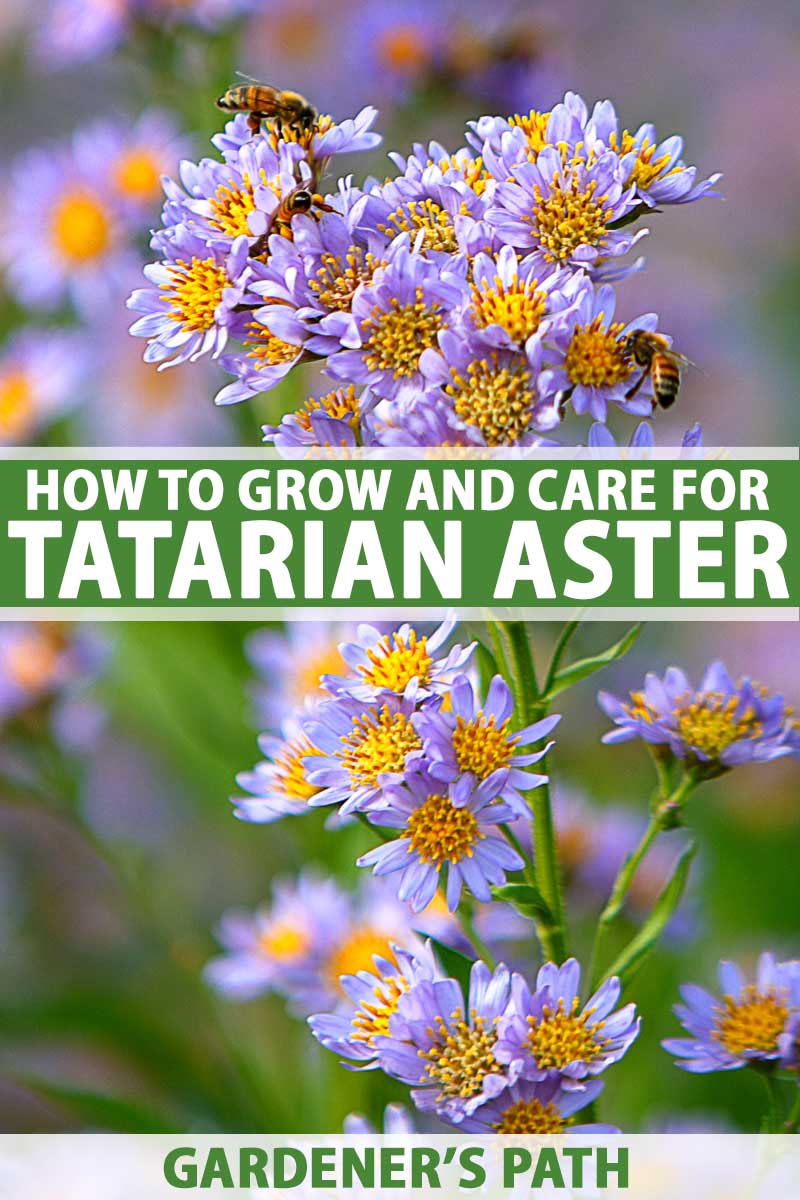

Flowers are about an inch in diameter and consist of lavender-blue rays surrounding a golden yellow center disk. The rays are wider and more upturned than the needle-like ones of the New England aster, and instead of being grouped conically, they form a flat-topped cluster.

Over the millennia, A. tataricus has been used by herbalists to make a root extract called “purple aster tincture” or “Zi Wan.”

Modern scientists have studied its potential benefit for those suffering from neurodegenerative diseases, and found that A. tataricus “produced an “anti-neuroinflammatory effect.”

Powdered products available today bear a disclaimer that strongly recommends use only under the supervision of a certified herbalist.

It’s quite likely that the Tatarian aster’s name dates to the thirteenth century, the time of Genghis Khan and the Turkish-Mongolian Tartars, many of whose descendants live in Tatarstan, along the Volga River in Russia.

What a bloodthirsty heritage for a little lavender-blue blossom!

But for all its sweet appearances, A. tataricus is tough as nails. Topping out at six feet or more, with a spread of three feet, it stands up to weather, pests, and diseases like a champ. From September to hard frost, it’s loaded with blossoms, and may consume all in its path if left undisturbed.

The growing season is long, with new shoots popping up in spring and flowers blooming non-stop from about September to the first hard frost. And unlike many asters that begin to look ragged by the time first frost arrives, this one stays first-day fresh the whole way through.

Tatarian aster has been in the United States long enough to have naturalized in much of the Eastern region. And while the species is not classified as invasive, it grows with vigor.

A dwarf cultivar, A. tataricus ‘Jindai’ is a smaller-statured variation of the true species that was first documented in the Jindai Botanical Garden near Tokyo, Japan.

Propagation

To grow Tatarian aster in your landscape, you have several preferred ways to begin that you may choose from:

Cutting

Division

Nursery plants

Starting with seed is not recommended, because cultivated varieties don’t usually produce “true to seed,” and fail to replicate the desirable characteristics of the parent plant.

To start with a cutting, snip off a new shoot in springtime, place it in rooting hormone, and then place it in potting medium to grow roots.

You may also divide a mature plant by slicing down through the roots, removing the division, and establishing it elsewhere.

And finally, you may purchase a nursery-grown plant.

How to Grow

After the last frost date in early spring, you may put rooted cuttings, divisions, or nursery plants into the ground.

Choose a location that receives full sun. This plant does well in a variety of soil conditions, but where conditions are too rich, it may grow rather leggy and need staking.

Excellent drainage is essential.

Space plants according to their mature dimensions. Both the true species and the ‘Jindai’ cultivar have a maximum spread of three feet, so leave at least three feet between plants.

Maintain even moisture during the initial phase, to facilitate acclimation to the garden. Once established, plants that receive occasional rain do not need supplemental water and demonstrate a fair amount of drought tolerance.

This plant spreads via a system of thick roots called rhizomes that fan out sideways. It naturalizes readily under ideal growing conditions.

Growing Tips:

This is an easy plant to grow when you provide the following:

Spring planting for firm establishment before winter

A location with full sun

Well-draining soil

Even moisture during establishment in the garden

Proper spacing for adequate airflow

Care and Maintenance

This plant is self-sufficient once established. However, there are a few tasks that will enable you to fully appreciate this plant:

In addition to spreading by rhizomes, it does self-seed. And as we’ve said, viable seeds that fall do not produce true replicas of the parent plant. You may deadhead clusters of spent blossoms before seed drop to reduce the possibility of variation, if this is something that you would rather avoid.

If you are growing in fertile soil, your plants may become leggy and unable to support their weight. Stake as needed for an attractive, compact appearance.

Consider pruning or “pinching back” true species plants in mid-summer to maintain a bushy shape. ‘Jindai’ cultivars don’t usually require pruning.

To contain this plant’s desire to roam, dig down around it each spring to destroy lateral roots that go beyond the foliage perimeter. Work the soil to remove the unwanted fleshy rhizomes.

In addition, you may divide plants every three years or so in the spring. Dig straight down through a plant, remove an entire section, roots and all, and relocate it or give it away.

Keep weeds and debris away from plants to minimize water competition, inhibit insect infestation, and maintain good airflow.

Cultivars to Select

There are two smaller-statured cultivars from which to choose. They are often referred to as Tatarian daisy.

‘Jindai’

A. tataricus ‘Jindai’, is 3 to 4 feet tall with a spread of 2 to 3 feet.

The smaller stature of this naturally occurring variation makes it suitable for beds, borders, and containers with a diameter of at least 3 1/2 feet. This compact variation of the true species seldom requires pruning or staking.

‘Blue Lake’

A. tataricus ‘Blue Lake’ has lavender-blue coloring and an even smaller height of only 2 to 3 feet.

It’s also great in beds, borders, and containers, and its sub-compact size makes it an excellent candidate for the cutting flower garden.

A. tataricus starter plants are available from IB Prosperity via Amazon. These will arrive in 2.5-by-2.5-by-3.5-inch pots, ready for planting.

Aster Tataricus, 30 Seeds

If seeds are what you’re after, these are available from PlantGrabber, also via Amazon.

Managing Pests and Disease

The A. tataricus species is not prone to pests or diseases.

However, asters in general sometimes fall victim to fungal conditions like powdery mildew, and fusarium and verticillium wilt. They may also suffer from nematodes, slugs, and snails that feed at the root level.

To avoid these issues, you’ll need to have proper spacing between plants for good air movement, and well-draining soil.

In the event of a problem, address the fungus with an organic fungicide, and apply diatomaceous earth to deter nibbling below ground.

There’s also a nasty condition that sometimes destroys plants altogether. It’s called aster yellows and is a bacterial disease borne by insects, including the aster leafhopper. It is incurable.

Providing appropriate sun, soil, spacing, and moisture will go a long way toward growing healthy flowers, foliage, and roots.

Best Uses

A tall plant that provides late season color makes an excellent back-of-border anchor. Its foliage forms a backdrop of green texture and movement through the summer, complementing lower plantings placed in front of it.

And when it blooms, the viewer’s eye is drawn upward along vertical stems to an attractive layer of lavender-blue accented by disks of gold.

This is also a wonderful choice for a meadow, where there’s room to spread and nourish multitudes of bees, birds, and butterflies that will happily pollinate your gardens in return for the feast.

Companion plants with similar cultivation requirements to A. tataricus include goldenrod, helenium, joe-pye weed, milkweed, ornamental grass, red valerian, speedwell, and sunflower.

Saving the Best for Last

There are loads of annuals and perennials with a claim to spring or summer fame, but stalwart bloomers that resist autumn’s chill are fewer and farther between.

Now, you’ve discovered a lavender-blue beauty that blooms profusely despite the rigors of shortening days and limited sunshine. Make room for it in your garden and you will be rewarded with repeat performances for years to come.

Tell us in the comments section below how this late-season bloomer will grace your outdoor living space this year.