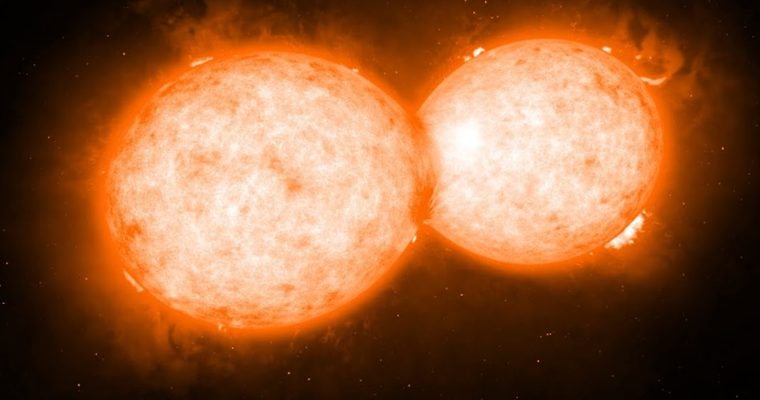

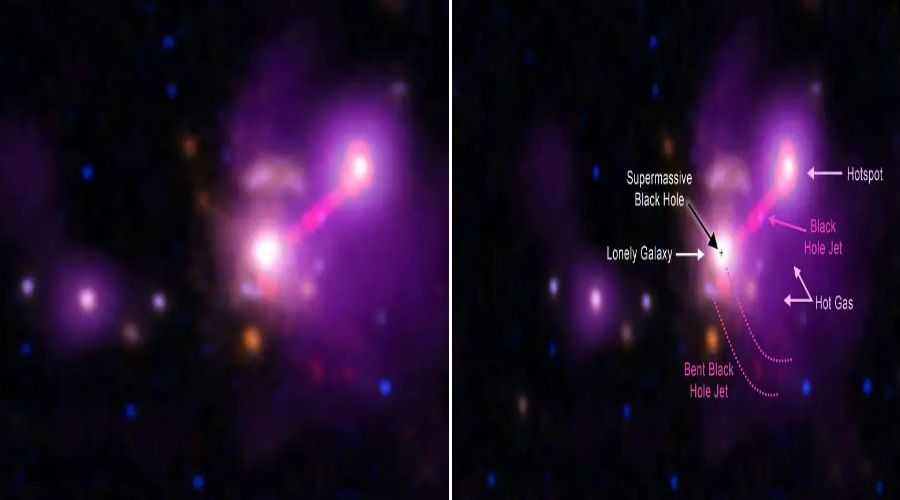

Supercomputer simulations on Frontera reveal the origins of ultra-massive black holes, the most massive objects thought to exist in the entire universe. Shown here is the quasar triplet system centered around the most massive quasar (BH1) and its host galaxy environment on the Astrid simulation. The red and yellow lines mark the trajectories of the other two quasars (BH2 and BH3) in the reference frame of BH1, as they spiral into each other and merge. Credit: Yueying Ni et al.

The ASTRID cosmological simulation, a massive simulation run on TACC’s Frontera supercomputer, is aiding in the investigation of ultra-massive black holes.

Ultra-massive black holes are the heaviest entities in the cosmos, with some weighing in at millions or even billions of times the mass of the Sun. Through simulations run on TACC’s Frontera supercomputer, astrophysicists have gained insight into the origin of these behemoth black holes, which formed around 11 billion years ago.

“We found that one possible formation channel for ultra-masssive black holes is from the extreme merger of massive galaxies that are most likely to happen in the epoch of the ‘cosmic noon,” said Yueying Ni, a postdoctoral fellow at the Harvard–Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics.

Ni is the lead author of work published in The Astrophysical Journal that found ultra-massive black hole formation from the merger of triple quasars, systems of three galactic cores illuminated by gas and dust falling into a nested supermassive black hole.

Working hand-in-hand with telescope data, computational simulations help astrophysicists fill in the missing pieces on the origins of stars and exotic objects like black holes.

One of the largest cosmological simulations to date is called Astrid, co-developed by Ni. It’s the largest simulation in terms of the particle, or memory load in the field of galaxy formation simulations.

“The science goal of Astrid is to study galaxy formation, the coalescence of supermassive black holes, and re-ionization over the cosmic history,” she explained. Astrid models large volumes of the cosmos spanning hundreds of millions of light years, yet can zoom in to very high resolution.

Study lead author Yueying Ni, Harvard–Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics, presenting at the 2022 Frontera User Meeting, Texas Advanced Computing Center. Credit: TACC

Ni developed Astrid using the Texas Advanced Computing Center’s (TACC) Frontera supercomputer, the most powerful academic supercomputer in the U.S., funded by the National Science Foundation(NSF).

”Frontera is the only system that we performed Astrid from day one. It’s a pure Frontera-based simulation,” Ni continued.

Frontera is ideal for Ni’s Astrid simulations because of its capability to support large applications that need thousands of compute nodes, the individual physical systems of processors and memory that are harnessed together for some of science’s toughest computations.

”We used 2,048 nodes, the maximum allowable in the large queue, to launch this simulation on a routine basis. It’s only possible on large supercomputers like Frontera,” Ni said.

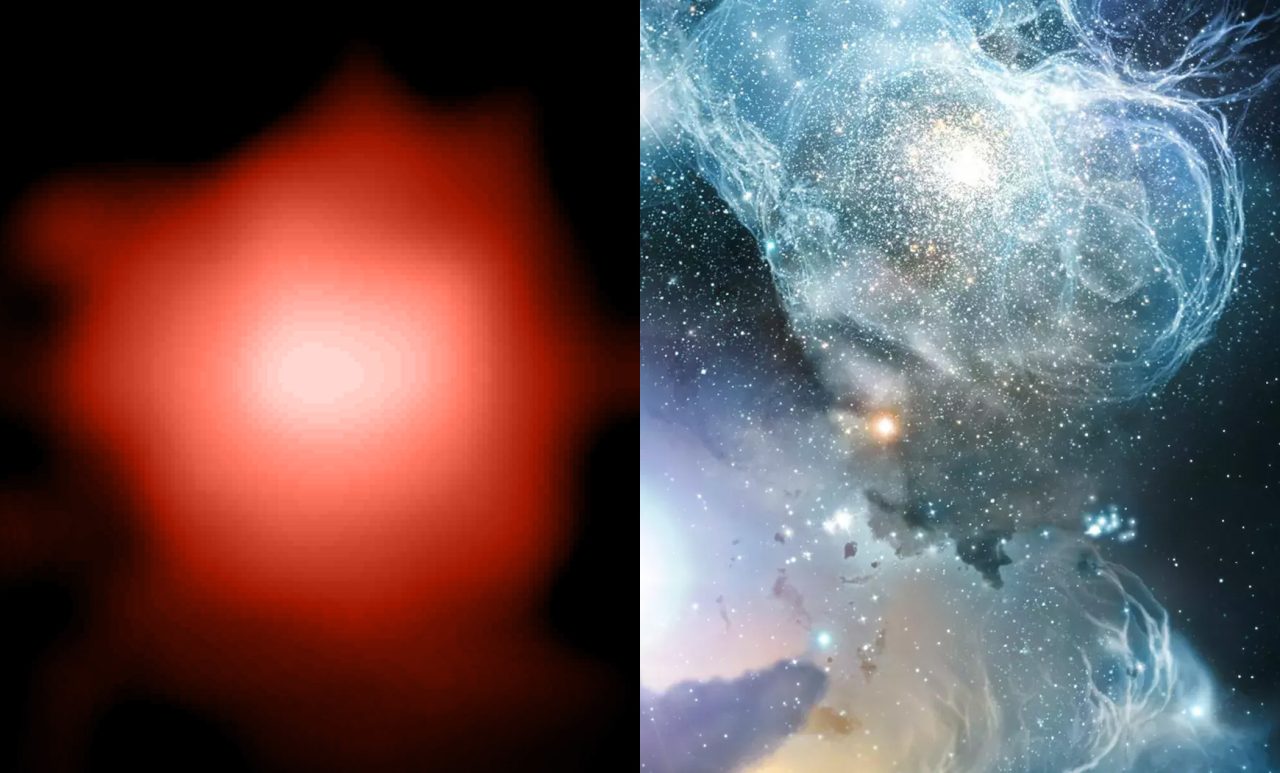

Her findings from the Astrid simulations show something completely mind-boggling — the formation of black holes can reach a theoretical upper limit of 10 billion solar masses. “It’s a very computationally challenging task. But you can only catch these rare and extreme objects with a large volume simulation,” Ni said.

“What we found are three ultra-massive black holes that assembled their mass during the cosmic noon, the time 11 billion years ago when star formation, active galactic nuclei (AGN), and supermassive black holes, in general, reach their peak activity,” she added.

About half of all the stars in the universe were born during cosmic noon. Evidence for it comes from multi-wavelength data of numerous galaxy surveys such as the Great Observatories Origins Deep Survey, where the spectra from distant galaxies tell about the ages of its stars, its star formation history, and the chemical elements of the stars within.

”In this epoch, we spotted an extreme and relatively fast merger of three massive galaxies,” Ni said. “Each of the galaxy masses is 10 times the mass of our own Milky Way, and a supermassive black hole sits in the center of each galaxy. Our findings show the possibility that these quasar triplet systems are the progenitor of those rare ultra-massive blackholes after those triplets gravitationally interact and merge with each other.”

What’s more, new observations of galaxies at cosmic noon will help unveil the coalescence of supermassive black holes and the formation the ultra-massive ones. Data is rolling in now from the James Webb Space Telescope (JWST), with high-resolution details of galaxy morphologies.

“We’re pursuing a mock-up of observations for JWST data from the Astrid simulation,” Ni said.

“In addition, the future space-based NASA Laser Interferometer Space Antenna (LISA) gravitational wave observatory will give us a much better understanding the how these massive black holes merge and/or coalescence, along with the hierarchical structure, formation, and the galaxy mergers along the cosmic history,” she added. “This is an exciting time for astrophysicists, and it’s good that we can have simulation to allow theoretical predictions for those observations.”

Ni’s research group is also planning a systematic study of AGN hosting of galaxies in general. “They are a very important science target for JWST, determining the morphology of the AGN host galaxies and how they are different compared to the broad population of the galaxy during cosmic noon,” she added.

“It’s great to have access to supercomputers, technology that allows us to model a patch of the universe in great detail and make predictions from the observations,” Ni said.