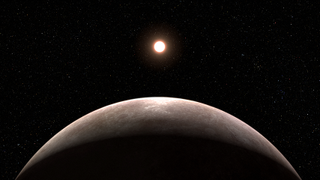

NASA’s newest space telescope has notched another milestone with observations of its first rocky world.

A little over a year after its launch, the historic James Webb Space Telescope has detected its first rocky exoplanet, and the distinction goes to LHS 475b — an Earth-size planet as hot as Venus located just 41 light-years away from Earth in the constellation Octans.

“I think we are just starting to scratch the surface of what is possible with JWST,” Jacob Lustig-Yaeger, an astronomer at the Johns Hopkins University Applied Physics Laboratory in Maryland and one of the lead authors of the study, told reporters on Wednesday (Jan. 11) at the 241st meeting of the American Astronomical Society in Seattle.

Webb’s design process began when scientists had identified only a handful of exoplanets, and the observatory wasn’t tuned to discover alien worlds. However, the telescope’s formidable optics, and particularly its ability to split light from a source by wavelength, make it a powerful tool for studying planets and planet candidates that scientists have already spotted.

So using Webb’s Near Infrared Spectrograph (NIRSpec) instrument, Lustig-Yaeger’s team looked for atmospheres on a handful of rocky Earth-size exoplanets. One of their targets was a planet called LHS 475b or GJ 4102b, hints of which had previously been spotted by NASA’s primary planet-hunter, the Transiting Exoplanet Survey Satellite (TESS) mission that launched in April 2018.

At the time, LHS 475b was just a candidate, not a confirmed planet. But it only took two transits of the exoplanet in front of its star for Webb to detect it, living up to its fame of being the largest and most powerful space observatory to date. “These pristine data help to validate and confirm the discovery of this Earth-size exoplanet,” Lustig-Yaeger added.

“These first observational results from an Earth-size, rocky planet open the door to many future possibilities for studying rocky planet atmospheres with Webb,” Mark Clampin, director of NASA’s astrophysics division, said in a statement. “Webb is bringing us closer and closer to a new understanding of Earth-like worlds outside the solar system, and the mission is only just getting started.”

An illustration shows the dip in light that the James Webb Space Telescope saw from the star LHS 475 as a planet passed between the star and the telescope. (Image credit: NASA, ESA, CSA, Leah Hustak (STScI)/Kevin B. Stevenson (APL), Jacob A. Lustig-Yaeger (APL), Erin M. May (APL), Guangwei Fu (JHU), Sarah E. Moran (University of Arizona))Searching for an atmosphere

An illustration shows the dip in light that the James Webb Space Telescope saw from the star LHS 475 as a planet passed between the star and the telescope. (Image credit: NASA, ESA, CSA, Leah Hustak (STScI)/Kevin B. Stevenson (APL), Jacob A. Lustig-Yaeger (APL), Erin M. May (APL), Guangwei Fu (JHU), Sarah E. Moran (University of Arizona))Searching for an atmosphere

And the Webb data does a lot more than merely confirm that the exoplanet exists. The observations also prove how revolutionary the telescope will be at sniffing out what gases surround an alien world — crucial information for understanding what a planet is like.

“Over the next few years and ultimately decades, the search for life on exoplanets will fundamentally rely on the detailed characterization of exoplanet atmospheres,” Lustig-Yaeger told reporters during the press conference.

The team observed LHS 475b as it transited twice in front of its host star, a red dwarf that the planet orbits every two days. The first transit occurred on Aug. 31, 2022, and the second one happened four days later, on Sept. 4. Lustig-Yaeger’s team recorded that 0.1% of the star’s light was being blocked by the planet over the course of its 40-minute transits. From that, the team calculated that the planet is almost the same size as Earth, with roughly 99% of its diameter.

A diagram showing the transmission spectrum of exoplanet LHS 475 b (in white) as compared with a pure methane atmosphere (in green), a featureless spectrum like that of a planet without an atmosphere (in yellow) and a pure carbon dioxide atmosphere (in purple). (Image credit: NASA, ESA, CSA, Leah Hustak (STScI)/Kevin B. Stevenson (APL), Jacob A. Lustig-Yaeger (APL), Erin M. May (APL), Guangwei Fu (JHU), Sarah E. Moran (University of Arizona))

A diagram showing the transmission spectrum of exoplanet LHS 475 b (in white) as compared with a pure methane atmosphere (in green), a featureless spectrum like that of a planet without an atmosphere (in yellow) and a pure carbon dioxide atmosphere (in purple). (Image credit: NASA, ESA, CSA, Leah Hustak (STScI)/Kevin B. Stevenson (APL), Jacob A. Lustig-Yaeger (APL), Erin M. May (APL), Guangwei Fu (JHU), Sarah E. Moran (University of Arizona))

To learn more about the planet’s atmosphere, the team combined data from two transits into one transmission spectrum, but didn’t find any molecules abundant enough to be detected by Webb — for now.

“The telescope is so sensitive and the data are so precise that we could have easily detected several different molecules, but we don’t see much yet,” Kevin Ortiz Ceballos, a graduate student at the Harvard Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics in Massachusetts, who performed one of the three independent data analyses, said in a statement.

The team’s analysis method looked at the amount of light blocked by the planet at specific wavelengths. What they were trying to see, Lustig-Yaeger said, was apparent increases in the planet’s size at wavelengths that certain molecules are known to absorb, “causing the planet to appear larger,” thanks to the contribution of the atmosphere.

Even without any detections, the team could use various models to rule out what’s not in the atmosphere. To do so, researchers focused on a specific feature in the transmission spectrum — a chart depicting how much light is blocked at each wavelength. A transmission spectrum might not be very interesting visually but can shed light on important information about a planet.

For example, researchers determined that LHS 475b cannot have an atmosphere dominated by hydrogen, like the atmospheres of the gas giants in our solar system. They also found that a methane-rich atmosphere like the one harbored by Saturn’s strange moon Titan is not likely because methane molecules are expected to block more starlight at certain wavelengths than the researchers observed.

An artist’s depiction of the exoplanet LHS 475 b. (Image credit: NASA, ESA, CSA, L. Hustak (STScI))

The researchers also modeled a couple possible atmospheres for LHS 475b that the Webb data couldn’t rule out. On one hand, Lustig-Yaeger said that certain features in the transmission spectrum could be produced by a thin atmosphere consisting of carbon dioxide.

On the other hand, the planet could also sport an atmosphere rich in carbon dioxide, like the atmosphere of Venus, he added. Such an atmosphere would produce a very flat, featureless spectrum, similar to what “we would expect for a planet that does not possess an atmosphere,” he told reporters, which provides an excellent fit to the observations as well. It could also explain why the planet appears to be what NASA called “a few hundred degrees” warmer than Earth.

Given these possibilities, LHS 475b “very well could be an airless body that has lost any atmosphere that it once had,” Lustig-Yaeger said. “But it also might possess a compact atmosphere that we are not sensitive to.”

Distinguishing the two scenarios would require “very, very precise data,” he said in a statement. While it’s hard to tell the difference just yet, astronomers hope to get more clarity during an additional transit scheduled for this summer.

“It is only the first of many discoveries that [Webb] will make,” Lustig-Yaeger said in a statement. “With this telescope, rocky exoplanets are the new frontier.”